"You can't act out Mr Angry for ever, like some on-the-nose ham. I was looking for an effective sort of detached tranquility"

- John Foxx on leaving behind punk

An interview with the eloquent Mr Foxx for Shock and Awe.

In one of the first Ultravox interviews (NME 1977) you talked about being fans of the Velvets and the Dolls. But generally your orientation seems much more English – England and Europe. Psychedelia and glam appear to be the primary and abiding influences. (English psych, mind – Barrett + Revolver rather than Jefferson Airplane and “Dark Star”!). Would it be fair to say you’ve never been very attracted to American pop culture or US rock? (Excepting of course New York – but then Manhattan isn’t really part of America, really. Judging by how the rest of the USA regards it.)

That Jefferson Airplane/ West Coast axis interested me not at all.

Britain and Europe certainly set the table. (As you say–New York/ Manhattan is

really a displaced European city, so I guess much of what came out of there,

including the Velvets/Dolls and much of the CBGBs scene, might be included.

Also - as we now know, most of those bands, including the Ramones,

Patti Smith, Blondie and Talking Heads, were reacting in their various ways to

a previous generation of British music – The Dolls intent on recovering the

Stones initial glam/punk snottiness and the Velvets titles showed Brit/Europe

reaction – Sacher Masoch /European Son poetics,

plus they were also reacting to press reports of feedback-era Who etc)..

The Velvets were a very glamorous band –Warhol and all, but it was

a dark sort of glamour. A new scene based in the Factory - in a then unknown

New York (or at least unknown to most Brits), where anything might happen. A

mythland in the making.

At that time I also remember thinking that the impulse to imitate

another culture meant you regarded your own as inferior. So I tried to re-imagine what

British/European popular music might have sounded like if America had never

happened –If we hadn’t been overcome by a tidal wave from such a powerful and

energetic culture.

That became part of the brief I gave myself in writing the songs

for the band. It took a bit of doing, but defining what you didn’t want to be

certainly helped to clear the water.

Mind you, just like

everyone else of my generation, I’d long been fascinated by mainstream Americana–

from sci-fi films and comics I saw in the 1950s, then the Bill Haley/ Elvis /Chuck

Berry explosion later. I especially

loved old blues records - John Lee

Hooker/Little Walter/Howlin’ Wolf era. They were so roughly recorded but had a

power and immediacy that more polished stuff could never reach. Those Chess-era

blues guys had a glamour all of their own – they wore big suits and ties,

pulled-down fedoras and operated in Chicago – ultra urban scene of endless

archetypal gangster movies.

All this stuff came from a very different place - so a white

Industrial North Brit kid would be daft to attempt imitation. But it was such a

weight and so powerful that it was difficult to see your way out - at

first. Post-Beatles and Psychedelia, the

only possible exit was to look in the opposite direction…

Germany was beginning to find its way out from the horror of its

recent past. The next generation had a seemingly impossible job to do in

defining themselves in absolute opposition to that era. There was a tremendous

energy there – the noises it was making attracted my attention. Since Brit

psychedelia had already moved there and left us with Prog, very early in the 70’s I realized the axis of

adventure in music had shifted to New York and Germany.

Then there was French chanson – those grand songs like the ones

that eventually became My Way and Life On Mars. Ferry picked up on these forms

more completely than anyone else and synthesized it all so beautifully, along

with a bit of Noel Coward glam, into Mother Of Pearl and Sunset etc. Then there

was Jaques Brel, Barbara, TV and Movie themes from the Third Man, The Killing

Stones, Radiophonic Workshop stuff such as Dr Who, Theramin sci-fi movie music,

The Tango, The angular beautiful music by Bernstein from West Side Story, and some Spanish and

Italian film music, too…An awful lot to reconcile. It took us a little while to

digest that lot and turn it into fuel.

The early Pink Floyd - all that early sunshine and shadow. Though

I disliked their tendency to lapse into blues forms on occasion, you had to

forgive them because the wild experimental stuff worked so well.

Live, they could make a timeless environment from feedback, smoke

and strobes. They introduced that summery, church-like form, too - Saucerful of

Secrets was the track – a rising Psychedelic hymn. Along with Tomorrow Never

Knows, it hinted at a revisiting of English church music, (There’s a line of

development there through Virginia Astley, Clannad’s Theme from Harry’s Game

and the Cocteau Twins. Much of it reached a dead end with Enya. I think some of that original spirit was

later recovered and condensed into Eno’s best piece - An Ending (Ascent)).

You always had to beware of

whimsy and there was plenty of that with The Incredible String Band and some of

Donovan’s later stuff - but there were great tracks from the Beatles and even

the Stones. Ray Davies did ‘See my friends’ – the very beginning of Psychedelic

Asian Drone and a superb record.

There was a fascinating sort of violence too, in the Syd-era Floyd

–lighting that cast massive threatening

shadows and blinding spectrum

strobes. Animalistic screeching,

disorientating echo effects and wild feedback.

The Velvets were doing The Exploding Plastic Inevitable the best

expression of violent light and noise. Momentarily, they and the Floyd

intersected at this point with The Who – feedback and Pop Art leaking into

experimental sound and Happenings. I

remember that, cumulatively, it all felt as though something unknown and

gigantic was arriving.

How involved did you get in the

Summer of Love and all that?

I went to the first 14 hour Technicolour Dream at Alexandra Palace.

It was a revelation.

Lighting by Mark

Boyle, Czechoslovakian art movies by

Walerian Borowczyk and Jan Lenica projected on the walls and the shock of Un

Chien Andalou by Bunuel and Dali, right beside new Avant-Rock. It all enlarged the remit of psychedelia into

a pan-European art movement and it certainly expanded my little mind that night

- I’m forever grateful for it - a real life changer. All of hip London in the

same place, lots of new connections made, then the Floyd coming on at dawn in

that huge overgrown Victorian church-like space. Perfect.

Afterwards everyone walked in a long dazed procession to the tube

at Highgate. It was a sunny, leafy, 1960’s tranquil London morning. Everything

was illuminated and I felt blessed - I’d met my generation - even though I was much younger than most

people there..

Later there was a 24 hour Technicolour Dream then to Christmas on

Earth Continued- I went to this at Earls Court if I remember.

After that, I occasionally bought Oz and International Times, had

the Martin Sharp Tambourine Man poster and The UFO freak out Butterfly poster,

went to many of the festivals and events. I printed my own posters and sold

them to existing stallholders to make just enough for the weekend. (Some of my

drawings were also reprinted in the underground press in the UK and US).

I was really searching for this world that I’d touched briefly at

Alexander Palace, but it was already evaporating. Later, I went to Woburn Abbey

and the first outdoor festivals until The Isle of Wight 1970, where it all

finally seemed to fall apart. Two people who hadn’t met before had sex in the

foam bank created as an entertainment. Most of the bands and music were a

disappointment. It had become a cheap circus and seemed so childish and

shoddy.

I went to see the Stones in the Park and they seemed untuned and

disconnected. King Crimson simply blew them away. A little later I went to my

last hippy party - everyone was lying around on the floor and no one spoke. The

place was dirty and reeked of dope and stale patchouli, the food was brown and

tasteless, the music had arrived at a set of conventions which left it stale on

delivery.

I quietly let myself out and wandered off home. Then came news of

Manson, Bader Mienhof, Patti Hearst, Manson and lots of other horrors from

various combinations of drugs, fanaticism, and careless or deliberate

abandonment of any moral compass.

Every aspect of the scene was also becoming colonized by slick

operators. A whole new breed of conmen and cheap dealers arrived, dressed in

the right clothes, saying the right things, but ever ready to take advantage.

It was easy for them because Acid had left many people in such a credulous

state.

Then the cults arrived - Divine Light and various Maharishis-

these took easy advantage of the fag end of a generation of fragmented,

Acid-blown brains. I used to see one little fat Indian lad - at the time touted as the latest divine

entity - being scolded by his parents

into his new Rolls in Highgate . You had to smile. It all fell down, down, down, by the

beginning of the 70’s

That was the end for me. I got a James Dean haircut and a complete

antipathy for that sort of sluggish hippy Bohemia.

Lost interest completely. Got into painting and drawing at art

school.

Oh Yes, that’s definitely true – the Bowie /Bolan bit came

directly out of a compound of mod sharpness and mid-hippy extravaganza.

The shops were very

important then, Kings Road was becoming the centre - Granny Takes a Trip etc

plus Portobello Road. A sort of 1930’s glittery smoke and strobe- lit

hallucinatory confusion of sex, gender and music evolved.

Hapshash and the Coloured Coat with The Human Host and The Heavy

Metal Kids were another influential style statement, even though the record

wasn’t much cop. Later, at the first Woburn Abbey festival as we were all

waiting to go in, I remember seeing a bunch of recent mods all newly decked out

in kaftans and those seashell beads, discussing their gear just as avidly as

they’d previously discussed tonic suits and tailors.

Some time in the late sixties, I also remember reading an article

in Vogue about this weird narcissistic cult of London mods who would gather to

dress up and pose in front of mirrors every day. One of them was Bolan before

he took up music..

Later, Bowie and Bolan both used both those periods as the launch pad.

Mission - retrieve glamour and mystery from the so

called ‘authenticity’ of early to mid 70’s rock

- All that Whistle Test denim and plaid. Dull Dull Dull. Two sharp ex- mods certainly weren’t going to

take that sort of neo- bureaucratic Puritanism for long.

Mod was really the first shot at glamour – working class kids able

to try out the existing style statement clothes from other tribes – Italian

driving heel shoes from Anello and Davide,

levis sta- prest, jumpers from W. Bill of Bond Street, etc. As well as

inventing their own styles and haircuts. It was a dressing in tribal symbols –

ironic and playful as well as ruthless and fast moving. You learnt how to read

the street – spot a new use of an existing cliché as well as a new invention.

Later, as a more extrovert evolution of that Mod gleaning, glam raided the dressing up box of the entire

history of glamorous imagery and recombined it all into a sort of eccentric

human collage – I always thought that Leigh Bowery was truly the ultimate

expression of all that.

Ferry came out of the mod thing too, but from a much more

intellectually demanding background at Newcastle School of Art. He used all his

mod and Hamilton honed visual acuity to take it all another step- further than

anyone at the time. - manifesting style as living pop art. He actually took pop

art back into the streets - making it a

million times more pervasive and effective than anything relegated to a

gallery.

Together with Anthony Price– another outstanding northern designer

– Roxy and Ferry repurposed every relevant image, every clichéd man-type and

tragic glam pose into a body of work as sleek as a starlets retouched press

shot. It had the faintest style echoes of that earlier, brief, Pop Art version

of the Who, which I also liked a lot, but it was much broader and more

pervasive. This one was alive, airbourne and fully contagious.

What are the initiating raptures and life-changing moments for you with music, and specifically with glam – particular concerts, or TV moments such as “Virginia Plain” on TOTP, NY Dolls on Old Grey Whistle Test, etc? Can you describe how they affected you, both in that moment and subsequently in terms of what you would go on to do?

Well, those two were absolutely seminal of course. The Dolls

clearly illustrated how trash, snot and sheer cheek are indispensible, while at

the other end of the spectrum, Roxy turned in a convulsive, momentary

compendium of all things wonderful. Two new universes available to an entire

new generation in just three minutes apiece. Very good going. A lot of new

bands got formed in Britain as a result of those two appearances.

Certainly – Chris Cutler has a point. The Shadows futuristic pop

dominated European music for years (By the way, another mentioned in the ads

was Billy Fury – take a look at his glitter suits in the 50’s and his guest

spot in that first-class rock-map and Essex vehicle ‘That’ll be the Day’ to see

what a blinder he was – and he wrote his own songs – a real first in those

days).

Rother loved early Shadows (as did Michele Jarre) It goes

everywhere - Marco in Adam and the Ants was clearly another Shadows fan, as is

Gilmour, and I’m sure Manzanera would own up if asked, so the threads go all

over - and all of these musicians had certainly grown up with that stuff on

every juke box across Germany, Britain and France.

This includes Kraftwerk - all their publicity shots are predicated

on Shadows early publicity. Ironic or not, the shadows visual and sonic style

was a major element in the making of Kraftwerk.

I think The Shadows

represent a manifestation of that cultural melting pot of Soho after WW2 -.

Italian suits from Jewish tailors. Italian shoes, haircuts and echo boxes.

Their material was composed by European emigres to whom rock’n’

roll was unfamiliar, but their heritage was the great European classical

composers and their own folk and religious forms, all evident in many of those compositions.

These were great, wide, cinematic melodies that gave an obligatory

nod to the new rock music, but their form reached back into middle Europe,

played on new electronic instruments with Cadillac styling and names –

Stratocaster for instance. This is also where popular music became completely

electronic – the electric guitar plus tremelo arm, recording studio and echo

effects, transformed it away from the sound of catgut and propelled it towards

the sound of theramin.

Of course this was glamorous in half-destroyed post-war cities,

and of course all young people wanted a new world, free from bombsites,

rationing and subdued parents. They wanted lights and joy and possibilities

In the early Shadows music you get the darkness and threat but you

also get the wonderful land - a vision of sharp coffee bars in neon cities,

cool people in cool clothes meeting, long cars going by outside.

Great titles - Frightened

City, Man of Mystery, FBI, Wonderful

Land. Altogether, it seemed incredibly futuristic and hip at the time.

Looking back they seem like the only true precursor to Kraftwerk -

clean, futuristic, separated sounds. Echo and reverberation – illusory

technological space used as an integral part of the music. Addressing urban youth and their dreams.

Mutated middle European melodies, a rigid urban futurist styling. Enjoyed

equally by bureaucrats in love and the avant-garde.

You talked in a NME interview of how

the group’s melodies naturally came out European in feel, specifically

Germanic. Billy talked about avoiding blues scales. You said, “We rejected all

those Americanisms that were going round at the time. And that's really why we

started off, because we wanted to make some English European music.” How important were things like “Song For

Europe” and Bowie’s shift from NYC / LA to Berlin?

Roxy gave permission to explore

kitsch and Euromusic, made it romantic and mysterious. Bowie’s shift was

a physical indication that he’d seen the future and it wasn’t simply Warhol any

more.

We’d decided before any of these, though, that we weren’t going

down Route 66. It was to be Route Nationale 1 and the M6.

I liked a few of the songs around that time – Golden Years

especially. But overall it was strangely unsatisfying - it seemed like some

sort of compromise to crack America. A bit too obvious. But it worked for him.

Absolutely. We were temporarily socially mobile because of a

unique historical opportunity and determined to taste it all.

At the same time we all

felt inadequate, self-conscious and unsure of the territories we were

accessing, so overcompensation becomes a ubiquitous symptom. You could be

forgiven though, because everyone instinctively knew exactly what was meant

when you overdid it – they felt the same, but didn’t dare –at first…

Art school was where you went when you weren’t sure what you

wanted to be, but cool. You met your generation and assembled some sort of

culture from all the trash that was floating under the bridge at the time. Whatever was going by that looked likely, you

incorporated. It was all you had.

Lots of ideas were swapped, sheer daftness and false starts could

be engaged in without ruin. You could practise subverting style conventions,

even ones which were considered radical.

Situationism was a practical strategy.

One example : - We were invited by a neighbouring art school to

their Happening and asked to bring some music and slides. Our lecturer at the

time, George Hollingsworth, asked what

we were going to take. I said a Ravi Shankar

album and oil and water slides - Psychedelia was new, so this was dead hip at

the time.

“How conventional”, said George.

“What would you do then?” I asked, feeling a bit miffed.

“Well, everyone should get

a short back and sides haircut and a grey suit and tie. The slides should be

Swiss typography, numbers one to ten. Music

- Bach cello suites. Everything mathematical and systematic. Totally in

contrast to everything everyone else will do. You all walk in single file,

everyone sits down together. Music

plays, numbers one to ten projected. Light go up. You all stand together and

walk out in single file”.

Brilliant, I thought.

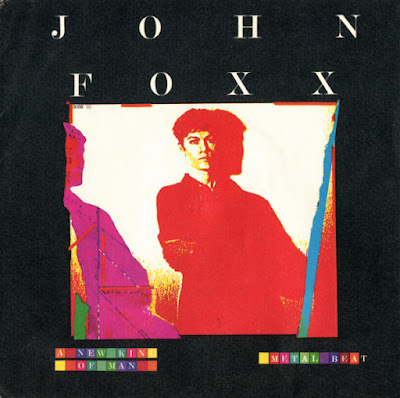

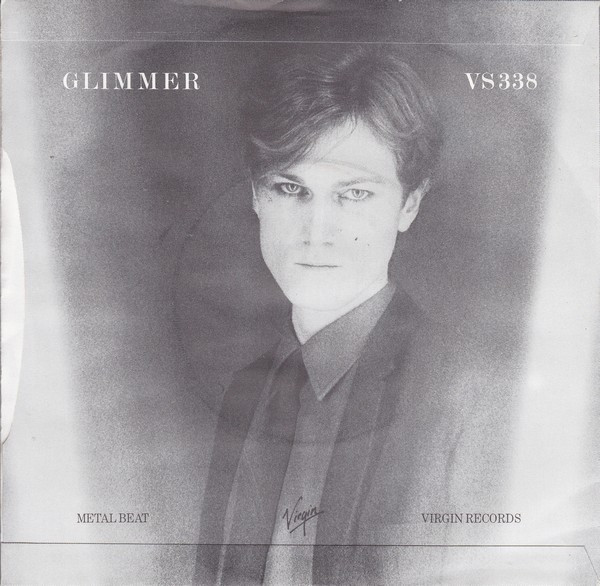

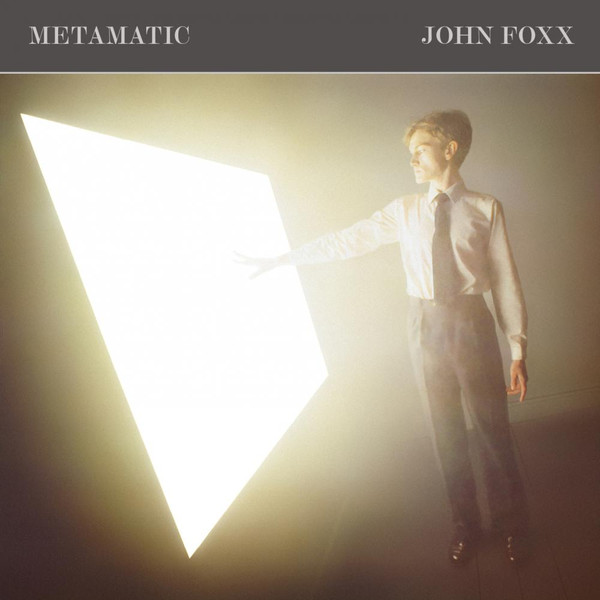

I actually put this into operation for Metamatic, around fourteen

years later. The convention then was ripped and torn Punk. I did the

oppositional move – electronics, a man in a grey suit. It worked.

Ultravox actually began as an art project. Richard Guyatt head of

design at the Royal College of Art had just given me the first year drawing

prize. Afterwards, he asked me what sort of projects I wanted to pursue.

A few days before, there’d been an interesting discussion of

‘Design for the real world’ - designing things you want to use and see, making

ideas become real, working with things you have some true experience of, the principle

of designing with your heart as well as your head, how to redesign yourself…

lots of fascinating new ideas at the time.

So said I’d like to design a rock band. “Great idea” he said. “Go

ahead”.

I was avoiding working in a factory or a mine.

Our parents were embedded in a post-industrial world that was

clearly limping to oblivion. You were slightly scared, wondering what might be

next and at the same time you were full of unfocussed energy, doubt and

evanescent courage, attempting to put all this together in some shape that

fitted the kind of life you thought you might want to live.

Northern industrial cities held tribes of kids who’d seen tv and

movies, wanted to get some of that and were prepared to remodel themselves in

the attempt. These bands seemed like a

gateway to another, better way of life. All over urban Britain, empty clubs

were available to try it out in. This became the network for the next stage.

The more general picture is, of course, that suddenly you are not

someone’s kid anymore. Hormones hit and you’re forced to begin to differentiate

yourself - to make your true self. Only you don’t know what that might be.

There are a number of off the shelf pop models available, or you can make your

own. These are all you have, so they have to do until real experience shapes

your real self. Then these identities

are usually let go gently.

Bands colonized this identity-blag window and acted as a common

focus for all the mess. It was their job. The really good songs felt like

personal messages to you from another world.

Things have changed. Then, media made you feel as if everything

was happening somewhere else - a million miles away from you and your tiny

life. You had to be truly dedicated to actually get there.

Now, the reverse is true – the biggest media are all to do with

social networking – it’s next door, happening all around, and now even

international events are predicated on and displayed through personal media.

You have a voice in it and a telepath’s world in your pocket.

Perhaps that’s why bands have little cultural impact or importance

anymore. They’re superfluous. Everyone already has the message. A song and an

image now take too long to carry it.

I stole it from Charlie and Inez Foxx – A great looking couple in

sharp silver outfits. I saw them supporting the Stones on an early tour in

Wigan. I thought Foxx was a great name and kept it in the back of my mind.

Much later I read an article about the new phenomenon of urban

foxes moving into London successfully. I liked their spirit and identified. So

that was it.

A new identity meant you could redesign yourself into something

more suitable for the new environment. The young lad from up north wasn’t

really up to the job.

Well, McLaren’s management and punk renaming was certainly a

deliberate parody of the 1950’s Fury/ Eager/ Quickly scene of Larry Parnes Svengali

management.

It’s a class thing too – working class kids are hidebound as any

other by a bunch of tribal rules of behaviour – you have to fight, can’t aspire

to get above yourself, poetry is nancy etc etc.

In order to ditch all that

you simply ditch the identity and you’re free. It’s a great liberation. And you

also come to represent an avenue of escape to others – but then, of course you

have to play that out in public too.

You inevitably make mistakes and make a fool of yourself at times.

Lou Reed had that great phrase ‘Growing Up in Public’ – that’s what you find

you have to do- no way out. All your worst and best moments writ large forever.

And there’s no way back. Gets tough on the fish counter after Top

of the Pops. Even if you do manage to succeed further than a hit single, you

can easily get isolated and then, without that essential external jibing and

criticism, begin to believe in the new version as real and the Top of the Pops

moment as some kind of peak experience. Utterly fatal.

A definition of a star is one that evinces a single human

attribute above all others - and often to the exclusion of all others. Marilyn

is sexy for instance – Johnny is angry, Sid is vicious. Dennis is a menace. Clint is cool. It’s the

Music Hall coming through. You invent an interesting character capable of

grabbing an audiences imagination and you sing songs about it. Of course, all this is instinctive at first.

Its only later you make those other connections.

If the character is good enough, they come to represent that

single behaviour to their consituency. They don’t need to be anything else.

Later they might modulate it a little - if they manage to survive, but their

purpose is really to be engaging enough for us to want to watch how they play

out their circumstances in their various worlds.

It was functioning – the company repaired Showroom Dummies. It was

called Modreno and was located in Albion Yard, off Balfe Street, an old

warehouse in a mews behind Kings Cross.

(I knew Ronnie Kirkland, the guy who ran it, because I used to

paint the faces of showroom dummies for a company called Adel Rootstein,

located first in Soho Square then In Kings Road Chelsea, and he worked there

too. You were paid per dummy and did a couple of hours a few evenings each

week. They used art students because the faces were done in oil paint).

The work kept me going

after I spent my grant on a pa system for the band. Then Ronnie formed a

breakaway company in Kings Cross. There was enough space to rehearse in the big

store-room. So all at once I had a base, a phone and a rehearsal room too.

Kings Cross was very rough in those days. It was the first time I

saw a woman squat down and urinate in the street in broad daylight. Each night,

as we exited the alley leading out of the yard, we’d pass by prostitutes

supplying the clients a swift knee-trembler, all lined up against the walls.

Modreno is also where I began to meet future members of The Human

League - they took a trip down with the dummies from Sheffield.

It was just a coincidence –we got Billy in as a keyboardist then

found his main instrument was Viola – I had that in right away because I loved

what Cale had been doing – the ragged violence of that sound through a

overdriven amp – beautiful.. The desire to change the entire format came a

little later.

Great fun. He’d just got the chop from Roxy and was still smarting

but had all these other interests. We soon realized he wasn’t that experienced

technically, but he had lots of nice bold ideas, some of which worked. The

purely technical stuff didn’t matter because we had Lillywhite along as

insurance. We negotiated our way through successfully and got on very well. I

was pleased he’d connected with Cale and Nico on one hand and with Tomorrow

Never Knows era psychedelia and a lot of Syd Baratt on the other. I always

thought he sang like Syd.

The call from Bowie to work on Low came just as we finished the

album, in September 76. We’d meet up again with Brian from time to time when we

were touring, at Connie’s studio in Germany, he was doing Devo and Music for

Airports there.

“I Want To Be A Machine” seems

like a key song, an anthem or mission-statement. Later, though, you told Nick

Kent that the sentiments came from “a very bad emotional period... a state of virtual manic depression,” caused

by “a relationship breakdown” that “had really cracked me up... I just wanted

to have all my emotions numbed.” And that you no longer felt that way and

indeed preferred “The Quiet Man” as a personal mission-statement. Can you

elaborate about “Machine” and also explain the Quiet Man concept of “the

onlooker, the observer” as ideal?

Well, Machine was a compound really - It was certainly a key song and a mission

statement.

I used to dismiss it as some personal episode - true, but really

it was a bit wider than just that.

It began from a quote by Gerard Malanga, then I realized I could

pour a lot of other stuff into the bottle – Marshall McLuhan etc. He was the

very first to talk about a global electronic nervous system and I found it all

very intriguing -what might it be like to become disembodied and detached – to

be purely objective and have no emotions?

- might there be some sort of new universal connectedness or

spirituality that all that other human noise made inaccessible?

I think it’s also built around leaving home and friends and the

fear of transforming into something unknowable or unrecognizable. A compound -

as these things often tend to be.

Ballard is really the end of glamour- the moment someone walks

into the ballroom with a gun. He’s also forensically fascinated by stardom and

celebrity.

Ballard was certainly an element in My Sex, as was Burroughs, but

really I was trying to describe how confusing the whole thing was. Also

beginning to examine how cities were shaping us in ways we barely recognize –

even into our erotic lives. All the

subtexts and tangled, unconscious attractions we were only beginning to become

aware of then. Ballard had done this with cars, architecture, films and

celebrities - especially in the Atrocity Exhibition - and that had

certainly jolted me to take it closer to

what I could see happening..

I’d also just realized that I was going to write about urban

landscapes from then on, so here was the first missive.

The Quiet Men was some kind of resolution to all that. A detached, calm, non-dramatic stance,

approaching invisibility. I really wanted to be anonymous and invisible. Some

sort of onlooker- almost a ghost..

I’d just got a grey suit

from Oxfam and began wearing it. After being onstage, and after all the frenzy

of punk, it was a great relief not to be noticed. Wearing that suit, you could

go anywhere without anyone giving a second glance. I loved it. You could watch

everything – all the little dramas that happen all the time in any city -

without drawing any attention to yourself.

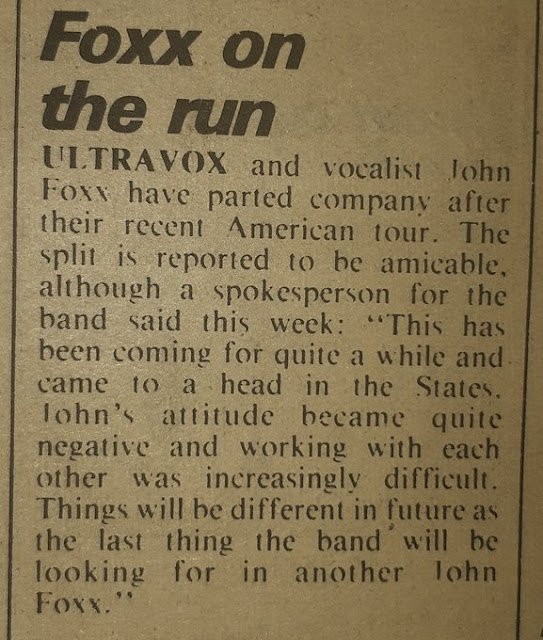

This was when I was discovering that I shouldn’t be in a band at

all. So it also became a symbol of wanting out of the whole thing. I think I

was burnt out at the time. The rock life was certainly not for me. I get psychically depleted by playing live

and have to go in for repairs.

(Ironically, the song doesn’t

sound frozen at all. It’s exuberant, full of fiery punk energy).

It was an aspect of machine, but just a little more specific– the

country was cold and grey, we were all going nowhere, and didn’t seem to care.

England seemed a very numb, dead place in 1976/7.

I think this song was the moment immediately before I decided that

all the angst of punk was better poured into some cool electronic stance, where

you didn’t act out the anger like some on-the-nose ham. You could be powered by

the same fuel, but drive more effectively and much, much further.

This was when all the anger of punk became transmuted into the

next phase of music - the cool world of electronics. In England, Punk didn’t

die, it simply changed form.

I always felt that Punk was a glam offshoot really. The Clash were

the trailer park sons of Presley and the Pistols were Ziggy’s feral kids.

I seem to remember that as a view from the rooftops.. You get a

new perspective. The world felt like it was all on the brink. Everyone seemed

far too complacent. It all felt very dangerous. This tiny island in a sea of

violence - all unconcerned and sleepy. We seemed so vulnerable and fragile. I

easily could see it all as derelict, as ruins.

Billy and I used to climb up on rooftops in Kensington when I was

still at Art College It felt like we were full of some kind of electricity.

London spread out, all lit up. Some

nights you’d feel you could see everything, even the future.

We’d see how far we could get over the rooftops. Through windows,

down corridors and hotel kitchens. We got all the way to the Dorchester one

night - ended up playing the piano in the ballroom before being gracefully

ejected.

“Hiroshima Mon Amour” : Roxy had done “2HB” but I can’t think of an example before “Hiroshima” of a song that directly references a specific film. How much did cinephilia feed into Ultraxox? The all-night movie houses and art cinemas of London and other major cities were crucial spaces at that time, right?

Oh yes – Lots of all-nighters at the Palace, Kings Cross. They

showed Euro art movies - Aguirre, The

Wrath of God etc as well as Warhol and other New York stuff, and Horror and

Sci-fi and B movie nights. Because of the terminal times, they quickly became

truly sleazy drug and drink -addled events.

There were more civilized venues too, like the Hampstead Everyman

and that Screen chain that Romaine Hart ran. Portobello Road, Baker Street - and Screen on the Green, where she put on

one of one of the first Pistols gigs.

I wanted the songs to be like small strange art movies – open with

a theme, establish characters and a world for them to operate in, then some

kind of resolution – or not. End theme. Fade.

I liked both for different reasons. Kraftwerk because they were

free of the clichés of the time and Neu! because they seemed to point to the

next stages of rock - incorporating technology and synths.

Kraftwerk were certainly the more glamorous. The world they

indicated was unreachable but recognizable and uniquely theirs. Its frontiers

coincided not at all with any rock world, or other media construct, bar early

Hollywood. They were aloof and the image had a sort of beauty not seen since

the golden days of Hollywood -the beauty of high definition and fine styling, like

an expensive automobile. Like Tamara de Lempicka’s self Portrait in the 1930’s.

Even so, I felt there were more possibilities from Neu!. There were hinted but unresolved directions

everywhere in their music. By contrast, Kraftwerk seemed likely to become a

closed system because of that lack of connection, the high definition, and its

own detectably rigid brief.

Of course. But the press at that time was a knockabout playground

and you simply accepted that. We’d begun to understand that many journalists

were still reeling from punk and hadn’t yet assimilated that, even after it was

clearly burnt out. Only one or two ever bothered to listen to anything that

came from outside England and America. Whoever invented that New Wave tag

solved the problem.

You can’t act out Mr Angry forever. I was looking for an effective

sort of detached tranquility. Where you stood on top of a moving, powerful wave

of music rather than trying to thrash it from behind in a frenzy. We felt we

arrived at that in Systems of Romance. We felt we’d consolidated on that album.

To us, it was a clear indication of the future. Even so, most of the press

didn’t know what to make of it at the time. Other bands and musicians certainly

did, though.

Did you feel any commonality with other “late glam” bands who initially had rough treatment from the press, like Japan, or Doctors of Madness? Japan in particular seem like possible kindred spirits – initially hugely inspired by the New York Dolls, starting out quite raunch ‘n ‘ roll and then getting more electronic / exquisite.

Well, we were never exquisites. I think we were mostly out on our

own.

It’s true that Japan were traveling a similar trajectory for some

time and we respected them and thought they were good, but we diverged as we

became more austere and they became more glamorous. I was determining Ultravox

be a new kind of electron-rock band and finally got to it on ‘Systems’.

What did you feel about the New

Romantics, Visage, et al ? The reference points and influences were similar but

often done rather clumsily and tackily.

The visual stuff from Steve Strange was imaginative for the time.

It was his vehicle of course, but the music was built by capable hands – Bill,

Midge, Rusty, Dave Formula, Richard Burgess etc. Fade to Grey was successful -

Moroder Meets Systems. The rest seemed uneven. Perhaps there were simply too

many cooks involved in that particular broth.

I thought the New Romantics was partly derived from Systems of

Romance, as was much of the form of the music. It was all good fun, even though

it was really nothing to do with what we were about.